URBiNAT cities through the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic

As COVID-19 tore across Europe and the world it struck at the heart of our societies, taking lives and revealing in a harsher, more uncompromising light the extent of social, economic, and environmental disparities within our communities. In some sense, the pandemic spread indiscriminately. Yet, it is clear that factors such as income level, housing type, neighborhood, and other socioeconomic variables would (once again..) determine starkly different levels of exposure or risk. Individuals, families, and communities have not suffered the effects of the pandemic in the same way. But what does this really mean? How have people coped with the restrictions imposed by COVID-19 mitigation policies? What lessons can we draw from this period?

The seven URBiNAT cities – Sofia, Nantes, Porto, Brussels, Siena, Høje-Taastrup, and Nova Gorica – give us a picture of the repercussions, challenges, responses, and alternatives that emerged with the pandemic. In this series of seven posts, we share the main measures implemented by local municipalities, and some stories to inspire alternative and cooperative ways to live together (in) the city. The full version will be available in URBiNAT’s deliverable related to the compilation and analysis of human rights and gender issues to be released in 2021. (https://urbinat.eu/resources/).

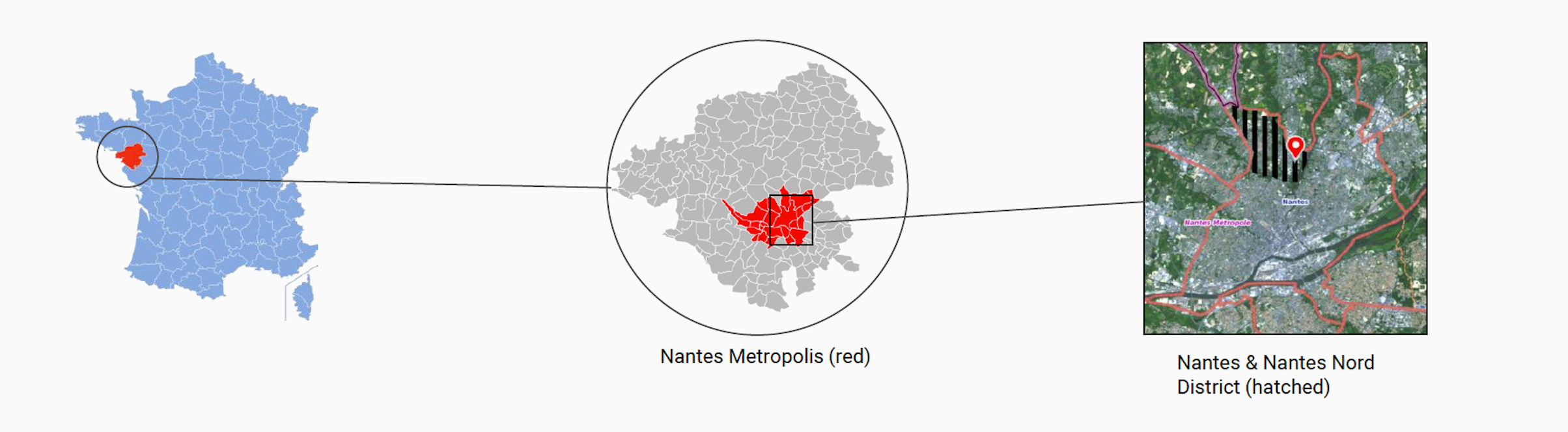

Brussels (Belgium)

Laetitia Boon and Sassia Lettoun, from the Municipality of Brussels, shed some light on increased and new challenges felt by the populations of the URBiNAT intervention areas, and on inspirational solidarity initiatives that helped overcome those challenges while also inspiring and teaching lessons for the future.

Large sections of the population had to deal to increased challenges due to the pandemic crisis. Loss of employment, for example, affected more precarious workers and workers in the tourism, food, and cultural sectors, as well as undocumented people. A decrease in local economic activity forced many small businesses to bankruptcy, partially due to not being able to pay the rent on their spaces.

The use of public space became challenging as physical distancing measures were increasingly enforced, and people stayed at home. This posed other challenges since the size of housing, the density of occupation, and working or attending school from home were particularly difficult for social housing populations. Homeschooling was harder for some families due to limited access to technological devices or parental support. Social isolation of older adults was another area of increased challenges, including mental health problems associated with the pandemics or prejudice and fears against care homes for the elderly.

It is noted highlighting that the worst-paid people were also the ones who continued to have to work, but most children could not go to school. Also, the larger interpretation of ‘family’ and the necessary social circle for social, mental, and economic solidarity purposes must have affected these populations to a certain degree, as the mandatory sanitary measures were based on the nuclear family and an individualistic mindset. For example, grandparents taking care of their grandchildren were not allowed under the strongest restrictions.

Gender-based violence was accentuated by the lockdown, and police control aggravated the situation of some populations that were already disproportionately controlled particularly racialized youth.

The Municipality tried to cope with these challenges in different ways. The public social welfare center (CPAS) offers financial support to those who find themselves in economic difficulties. A ‘Covid social action unit’ supports inhabitants who suffered materially, financially, medically, or psychologically. Other initiatives include shopping support for older adults by the community centres, the cancellation of rent for some commercial spaces during the lockdown by the housing management department, an economic recovery plan to businesses within the framework of a partnership between the municipality and the regional government, involving different dimensions such as listing local businesses on a new website, commercelocal. brussels.

BXL gift cards' - initiative of the City of Brussels to support local traders

A moratorium on evictions for the months of the lockdown allowed precarious households, squatters, and temporary occupiers to stay in their spaces and maintain their activities, often with a positive social impact on their surroundings in the case of collectives providing services such as food or masks distribution. The Municipality also installed more drinking water fountains and developed a strategy to distribute meals. Cycling paths were increased in length and number, responding to the reduced access to public transport.

The Brussels-Capital Region developed a ‘Thank you’ campaign to all the people of Brussels for what they have done so far and to ask them to persevere. Posters, videos, banners and other materials are available to do the same and be used by all. Source: https://coronavirus.brussels/

To ensure the continuation of projects that were already active, or to launch new projects, the Municipality had to think creatively and make the most of partnerships with associations working in direct and regular contact with inhabitants, such as the Bravvo association, fighting against social exclusion and the feeling of insecurity, social cohesion projects involving different associations and Brussels Housing, the Open Environment Actions, private services approved by the Wallonia-Brussels Federation that support young people in diverse ways, the health house/medical house, which practice preventive local medicine accessible to all, or the non-profit organisation Coin des Cerises, a community mental health project.

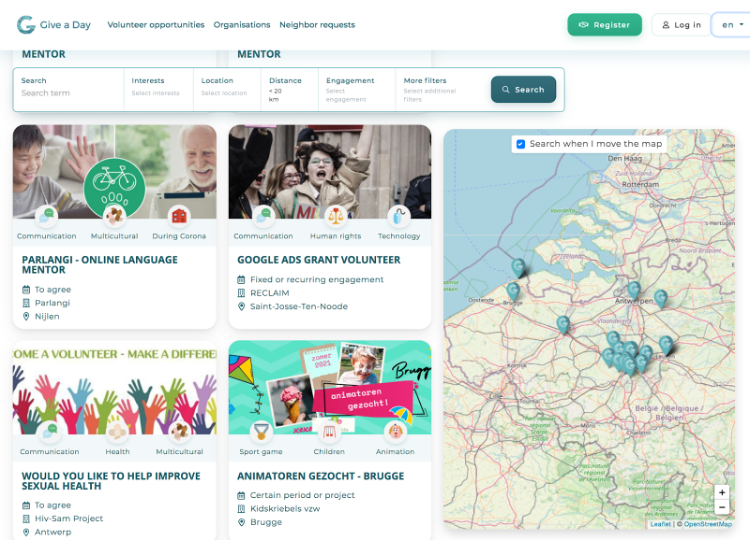

Many solidarity initiatives were launched or supported by the Municipality. Among those, the website solidair.brussels gives an overview of solidarity initiatives all over Brussels, the website www.impactdays.co/en/brusselshelps/, was much utilized to coordinate solidarity efforts, or the ‘neighborhood committees’, a solidary activity run by citizens. Citizen or associations-led solidarity initiatives were essential to cope with the crisis in many different ways, including the production and distribution of masks, actions of recognition for essential workers and of social strengthening, support to businesses, donation and distribution of food, computer devices, and other donations.

Smart volunteer matching platform - Brussels helps/Give a day: citizen or associations-led solidarity initiatives were essential to cope with the crisis Source: www.impactdays.co/en/brusselshelps/

The social impact of this crisis also raises difficult questions. How to recover from the fear of the other? How to face the upcoming recession? How to avoid disregarding essential societal changes? Will we return to an explosion of mass consumption? How are we going to work from now on?

Looking to the future, we may hope to develop resilient social and solidarity economies that can help us cope with these crises. We can build on lessons learned, become more resilient, and take action. Because we know now that the capacity of public institutions and of citizens is immense, and budget can always be found to support those in need, that solidarity initiatives are possible, valuable, and necessary for facing these crises together, that we can live with much less, degrowth and ‘happy sobriety’ is possible. What we need is access to health, education, culture, and other people, but not necessarily goods. It is not impossible to put values before money.

Social help during the Covid-19 crisis from Public Welfare Centre of the City of Brussels, Source: https://www.brussels.be/

Promotion of cycling: closing of Bois de la Cambre to cars. Demonstration bike ride - Critical Mass Brussels “Fight for your right to ride, every last Friday of the month”. Source: picture from Facebook page @criticalmassbrussels

This blogpost was elaborated by Rita Campos (CES-UC), based on the interview of Laetitia Boon and Sassia Lettoun (Municipality of Brussels), and conducted in the frame of task 1.5 (inclusion of cross-cutting dimensions human rights and gender) and its corresponding deliverable D1.8 (compilation and analysis of human rights and gender issues) to be released in 2021.

Comments Welcome!

Do you live or work in Brussels? We would love to hear from you! Did you feel the challenges described below? What lessons did you learn? What would you like to add to this picture?

Do you live or work in another city? We would love to hear from you also!

How would you describe the challenges and opportunities that emerged with the pandemic in your city? Were/Are they similar to those in Brussels?